In 1994, people thought electric cars were something that you plugged in. How that has changed. The electric cars of tomorrow will be powered by hydrogen fuel cells, at least that’s what the auto manufacturers are telling us.

Fuel cells rolled onto AI’s cover in June of 1999 under the headline “Here Come Fuel Cells.” But the Jeep Commander concept SUV, designed to demonstrate that this new low emissions technology could power a big truck, only ran on battery- supplied electricity. It made its hydrogen in theory, from an on-board gasoline reformer. Fuel cells graced AI’s cover again in 2002 as General Motors R&D Chief Larry Burns, rode the Autonomy “skateboard” onto the February cover. Autonomy promised to not only make hydrogenpowered vehicles a reality, but also promised to reinvent the automobile as we know it.

|

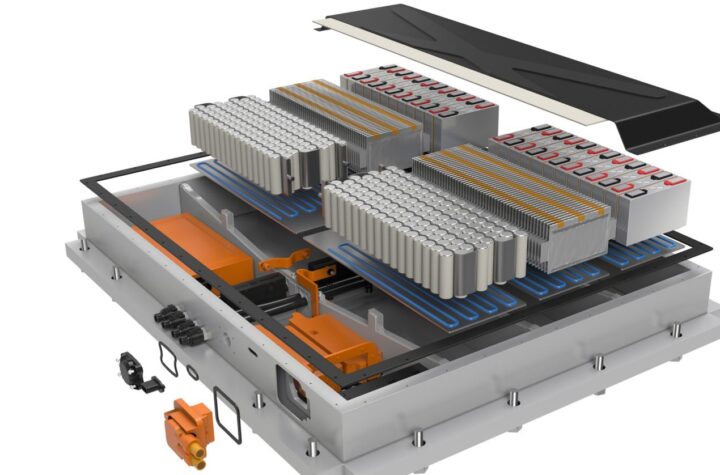

| First came Autonomy, then HyWire, now Sequel, GM’s latest take on a real-world purpose-designed fuel cell-powered vehicle. |

By this time, reformation systems had been replaced by on-board storage of gaseous or liquid hydrogen in specially designed high pressure tanks.

Pulling the plug on electric cars

GM is no stranger to electric cars. They developed the two-seat EV1 and began leasing the vehicle in 1996 in California and Arizona. Though EV1 did create a loyal following among the 800 or so lessees, battery technology never caught up and with a range only about 95 miles to a 6-hour charge, GM cancelled the program. While most of the vehicles are parked in the desert at GM’s Mesa, Ariz., proving ground, a fleet of more than 100 are being used by employees and some state and local agencies in Massachusetts and New York to gather coldweather performance data that will be used in hybrid and fuel cell development. Like EV1, most all of the OEMs have abandoned their electric vehicle programs concentrating on hybridelectric and fuel cell vehicles.

HEVs: The Road to Fuel Cells

The Honda Insight and Toyota Prius hybrid-electric vehicles (HEV) faced off on AI’s December 1999 cover. Honda’s lightweight two-seater was designed for the highest possible fuel economy while Toyota put its first generation Hybrid Synergy Drive system in a five-passenger sedan.

Honda followed Insight with a hybrid Civic in 2002 and Toyota launched a redesigned Prius in the summer of 2003. Ford joined the fray with a hybrid Escape that went on sale in the fall of 2004 and Honda added a hybrid Accord to its lineup a few months later. Toyota will launch a hybrid Highlander and Lexus RX400h in 2005. Nissan has licensed Toyota’s system for the 2006 launch of a hybrid Altima and a GM/DaimlerChrysler joint-development project will bring a full-hybrid GMC Yukon/Chevrolet Tahoe to market late in 2007 followed a month later by a Dodge Durango. Anthony J. Pratt, senior manager, global powertrain for J.D. Power says that sales are expected to hit about 400,000 units by 2008 which will represent roughly 2.5 percent of sales.

While hybrids will remain a viable alternative technology going forward, they are also the test bed for the same power electronics that will help propel fuel cell vehicles.

The Hydrogen Highway

Not all fuel cell vehicles are quite as radical as HyWire. In the last two years, small fleets of fuel cell cars have driven out of the laboratory onto the world’s roads, many based on current vehicle platforms such as DaimlerChrysler’s Mercedes A-Class-based NECAR 5.

Honda FCVs are being used by the city of Los Angeles. A GM Opel Zafira-based Hydrogen 3 was leased to FedEx in Japan for a one-year trial study and one Hydrogen 3 vehicle recently completed a 6,200-mile marathon run from Norway to Portugal. Ford Motor Company is building a fleet of 30 Focus fuel cell vehicles that will be split between Southeastern Michigan, Sacramento, Calif., and Orlando, Fla., for real-world testing.

While experts don’t doubt the industry’s ability to eventually design and build an affordable fuel cell vehicle, there are still a few major hurdles to get over. On-board hydrogen storage is far from cost-effective as exotic materials like carbon fiber and Kevlar are used to make tanks that cost thousands more than conventional gas tanks. Safety concerns still loom and the monumental task of building a national hydrogen infrastructure will only serve to delay mass commercialization.

North America’s first commercial hydrogen station, a project jointly developed by GM and Shell Oil, opened in Washington, D.C., a year later than originally planned due to red tape surrounding the codes and standards pertaining to hydrogen storage. As hydrogen companies push to build more stations they will surely run up against the same problems in every state and county. The same will hold true for those seeking permits for home refueling stations.

While the experts do see an increase in fuel cell fleet activity, most don’t see any kind of consumer or mass-market application before 2020.

And as GM’s Larry Burns points out, possibly learning from GM’s ill-fated EV1 electric car program, developing a cost-effective fuel cell-powered vehicle won’t necessarily guarantee success. “It’s very, very important to understand customers and understand what’s going to excite them going forward,” says Burns.

More Stories

Your Guide to Filing a Car Accident Claim

Steps to Take Immediately After a Car Accident

What Makes SUV Cars More Prone to Accidents?